What is Dada (Dadaism)?

Dada (or Dadaism) is an avant-garde literary and artistic movement of the 20th Century, developed between the 1916 and 1922, as a revolutionary and critical rejection to the brutality of the First World War.

The origins of the term are still unclear and there are various interpretations under consideration: Dada could derive from the non-sense onomatopoeic expression ‘dada’, one of the first words used in children’s language, recalling the absurd and playful roots of the movement.

It could literally be translated in a double statement in different languages (in Russian or Romanian it means “yes-yes”; in German “there-there”), evoking the distinctive internationalism of the artistic current.

Other sources cite the random and irrational origin of the name, obtained by the founding members by casually opening a page of a French-German dictionary and finding the word dada, an informal French term for a hobby horse.

Notable Dadaist Artwork

“Bicycle Wheel”, Marcel Duchamp

“Fountain”, Marcel Duchamp

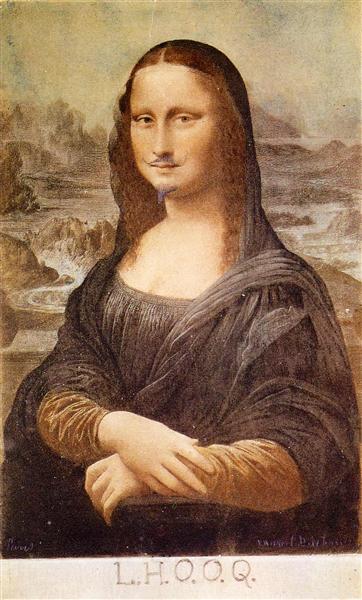

L.H.O.O.Q, Mona Lisa with Moustache, Marcel Duchamp, 1919

Construction for Noble Ladies, Kurt Schwitters, 1919

Merz Picture 32A (The Cherry Picture), Kurt Schwitters, 1921

Indestructible Object (or Object to Be Destroyed), Man Ray, 1923

Spirit of the Age: Mechanical Head, Raoul Hausmann

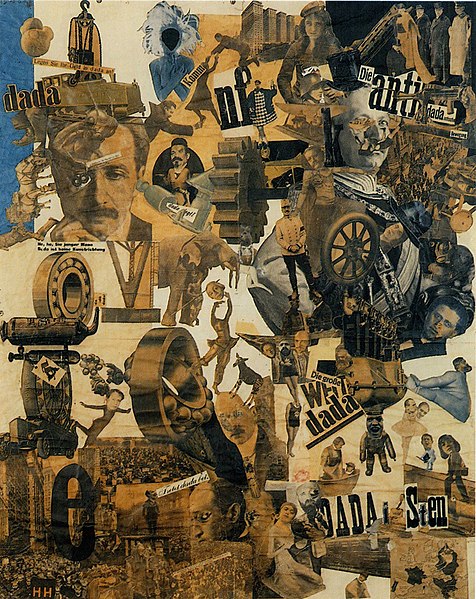

Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Epoch of Weimar Beer-Belly Culture in Germany, Hannah Höch, 1919

History of Dada (1916 – 1922)

The Dada movement was formally founded in Zürich in 1916, by a group of artists and poets who rejected the violence of the First World War and the absurdity of modern capitalist society, seeking refuge in Switzerland. Born in the context of a neutral country, the movement became international at the end of the war, spreading to Germany, France and the United States.

The official date of birth of Dadaism coincides with the organization of the first Dada evenings by the theater writer Hugo Ball and the foundation of the Cabaret Voltaire, the satirical night-club that became the main center of Dadaists’ radical activities.

At Cabaret Voltaire, the group, originally composed of Hugo Ball and the artists Jean Arp, Hans Richter, Tristan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck and Marcel Janco, organized experimental manifestations, which included nonsense poetry performances, provocative exhibitions, concerts, and conferences.

In July 1917, Tristan Tzara also published Dada, the first issue of the movement’s periodical, which continued to be published until 1921. The production of posters and magazines turned to be extremely important for Dadaism, not only from the content point of view but also of the aesthetics, which featured an extravagant typography in contrast with the norms of traditional design.

In 1918, Dada spread to Germany, establishing in Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, with Richard Huelsenbeck, Raul Hausmann, Kurt Schwitters, Max Ernst. In Berlin, the Dada Club had a strong revolutionary imprint, promoting overt political activities and propaganda. In Paris (1919-1922), the revolutionary demands of Dadaism were introjected by André Breton, Paul Éluard, and other French intellectuals, laying the foundations for what will be the subsequent Surrealism.

Parallel to the European experiences, Dadaism also spread to New York City, another refuge for artists escaped from the carnage of the war. By 1916, the United States became the center of the anti-art experiments of Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia. Experimenting with unorthodox materials as everyday objects, techniques like collages and photomontages, performances, Dadaists reinvented the concept of art, opening it to an unexplored range of mediums.

The readymades by Marcel Duchamp are exemplary, being manufactured goods that radically challenged the notion of work of art. Dada also inserted in the art process the concept of randomness and spontaneity, in response to the repressive strategies of logic and order.

According to Dada’s manifestos, the dominant characters of the movement were the disgust for traditional values and a subversive and nihilist charge. Dadaists wanted to subvert the illogic rules that have led humanity to the horrors of Great War. Their aim was to reveal the irrationality at the base of the bourgeois society, through nonsense, irreverent, and provocatory practices. Their acts of ruptures were not finalized to a new aesthetic system, but to the demolition of the already established one.

Dada’s spirit of revolt and lack of schematization had an influence on other avant-garde movements, such as Surrealism, but also on contemporary trends, such as Neo-Dada, Conceptual Art, Fluxus.

Notable Dada Artists

- Marcel Duchamp, 28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968, French

- Man Ray, August 27, 1890 – November 18, 1976, American

- Tristan Tzara, April 1896 – 25 December 1963, Romanian/French

- Francis Picabia, January 22, 1879 – November 30, 1953, French

- Jean Arp, 16 September 1886 – 7 June 1966, German/French

- Kurt Schwitters, 20 June 1887 – 8 January 1948, German

- Max Ernst, 2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976, German/French/American

- Raoul Hausmann, July 12, 1886 – February 1, 1971, Austrian

- Hannah Höch, 1 November 1889 – 31 May 1978, German

- Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, 12 July 1874 – 14 December 1927, German

Related Terms

- Readymade

- Collage

- Photomontage

- Assemblage

- Surrealism

- Futurism

- Fluxus

- Nouveau Réalisme

- Avant-garde

- Anti-Art

- Neo-Dada