Abstract art refers to works which do not represent reality in realistic visual forms. Instead, abstract compositions use lines, shapes, gestural strokes, colors or symbols to represent ideas. Abstract art has existed as long as human’s have been alive to create it. In fact, geometric abstract symbols have been found in ancient art.

In abstract art, lines, shapes, textures, forms, colors or patterns are used in different ways for both aesthetic and symbolic meanings. Mid-century Abstract artists did not depict reality as it was but rather as they conceived it to be. In some cases, they reduced meaning to simple lines and forms. The earliest forms of abstraction had references that could be identified and contained thoughts, ideas, feelings or imagination from the artist. Abstraction is not limited to painting, but is found in sculpture, printmaking and other forms of media and performance.

The term abstraction encompasses art that is not figurative, not objective and non-representational. That means that it typically contains no identifiable figures, objects or representations outside of the lines, shapes and brushstrokes. Also, abstraction as an artistic movement is wide and broad encompassing many different movements and styles that have developed from the late nineteenth century though till today. These movements and styles often overlapped growing into other movements as the artists who pioneered them shifted, evolved, or edited their practices.

In modern Western art history, abstraction only began to creep into art near the end of the 19th century. At the turn of the century as technological changes and scientific developments significantly changed the world, art also began to evolve. Abstract artists began to work for themselves.

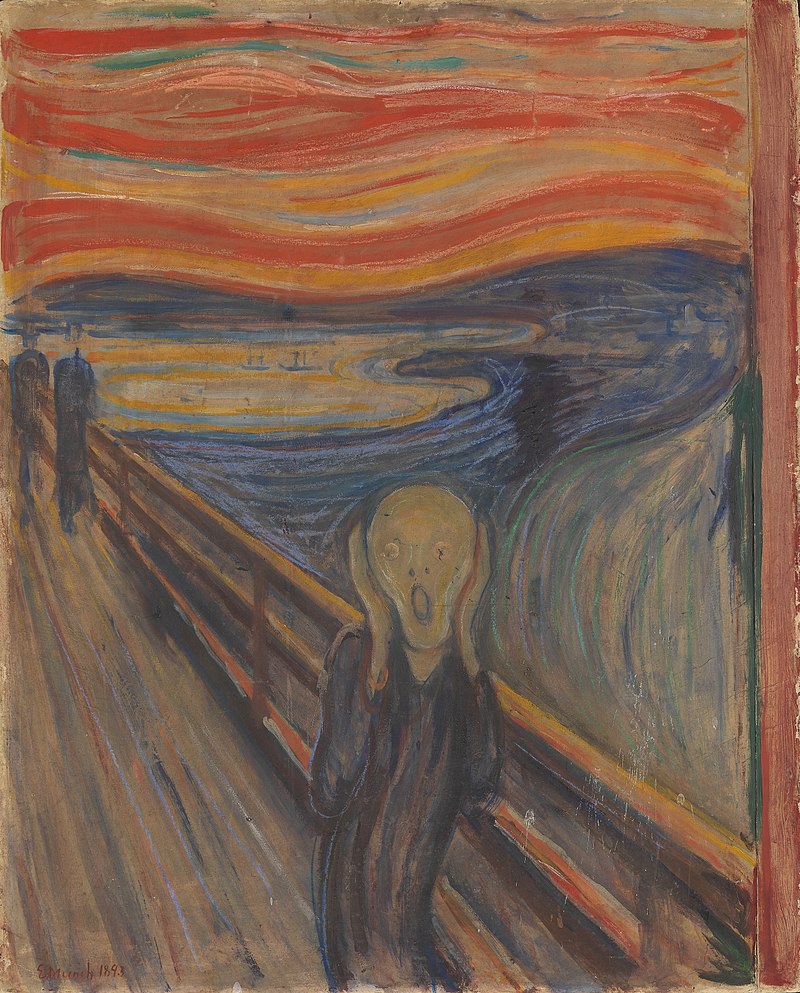

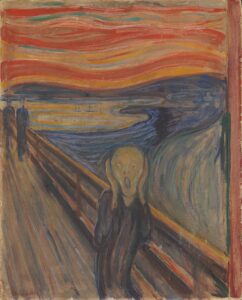

These artists began to push the boundaries of what could be done in art. Romanticism and Expressionism were two art movements led by the Avant Garde that paved the way for pure abstraction. Elements of abstraction crept into Expressionism. For instance, in Edvard Munch’s (1863-1944) The Scream (1893), the figure and the background are more abstracted then was previously done. These movements including Impressionism and Neo or Post- Impressionism were linked to Anarchy and the shift in political allegiances.

Emboldened by the success of these artistic movements from the Avant Garde, modern artists began to deconstruct their technique and the Post-Impressionist, Fauvist and Cubist movements were developed. Around the turn of the century, these movements began to develop into what would eventually be high modernism, which contained little to no symbolic reference, or even outside meaning. As the 20th century loomed, abstraction took two distinct courses. Those that sought to represent pure aesthetic forms and those that sought to use abstract forms to represent emotions or expressions.

There are several types of abstract art and different movements that grew out of this initial push away from figurative art. Some of the most prevalent forms of abstract art are Pointillism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Constructivism, Suprematism, Geometric abstraction, Dada, De Stijl, Concrete art, Tachisme, Abstract expressionism, Art Informel, Lyrical abstraction, Hard-edge painting, Action painting, Color field and Op art.

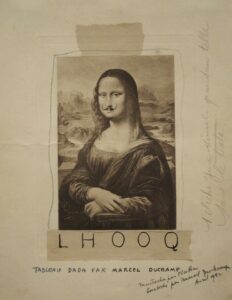

Famous artists who pioneered these movements include Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Piet Modrian (1872-1984), Lee Krasner (1908-1984), Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), Hilma af Klimt (1862-1944), Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) and many more.

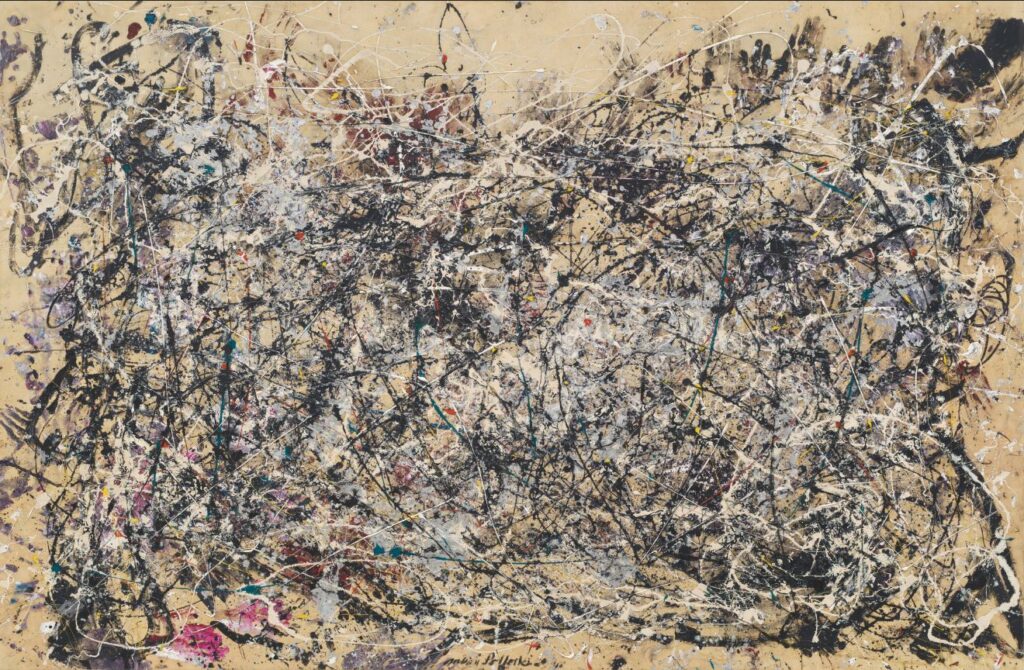

Typically, when people think of abstract art, Jackson Pollock’s Number 5, 1948 comes to mind. Pollock’s works represent the highest form of non-objective art and abstract painting as they contain no references to meaning or visual reality. Eventually, modern abstract art gave way to post-modernism, which reintroduced the figure and symbolic references, as artists and philosophers critiqued the emotionless modernism.

Contemporary art embraces abstract art, figurative art, as well as postmodernist ideas, but has moved away from abstract terminology and towards the notion of conceptual art. Behind each art is a concept or an idea. If you strip away talent and experience, the notoriously overvalued western culture viewpoint becomes obsolete and the idea behind the art is perhaps more important than the actual execution of it.

19 Types of Abstract Art: Characteristics and Artists

- Definition of Abstract Art:

- Abstract art does not represent reality directly but uses elements like lines, colors, and forms to express ideas, emotions, or concepts.

- It encompasses non-representational, non-figurative, and non-objective works.

- Historical Context and Origins:

- Traces of abstraction appear in ancient art, but it became prominent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Influenced by Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, and Cubism, abstract art challenged traditional artistic norms.

- Two Directions in Abstraction:

- Pure Aesthetic Forms: Focus on color, lines, and shapes (e.g., Geometric Abstraction).

- Emotional Expression: Represents feelings or concepts (e.g., Abstract Expressionism).

- Notable Movements and Characteristics:

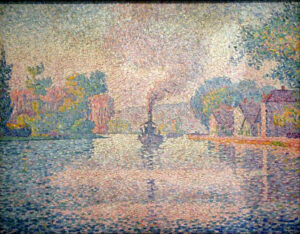

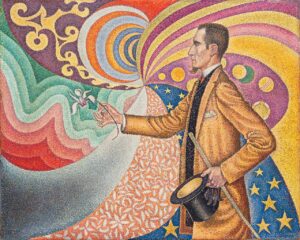

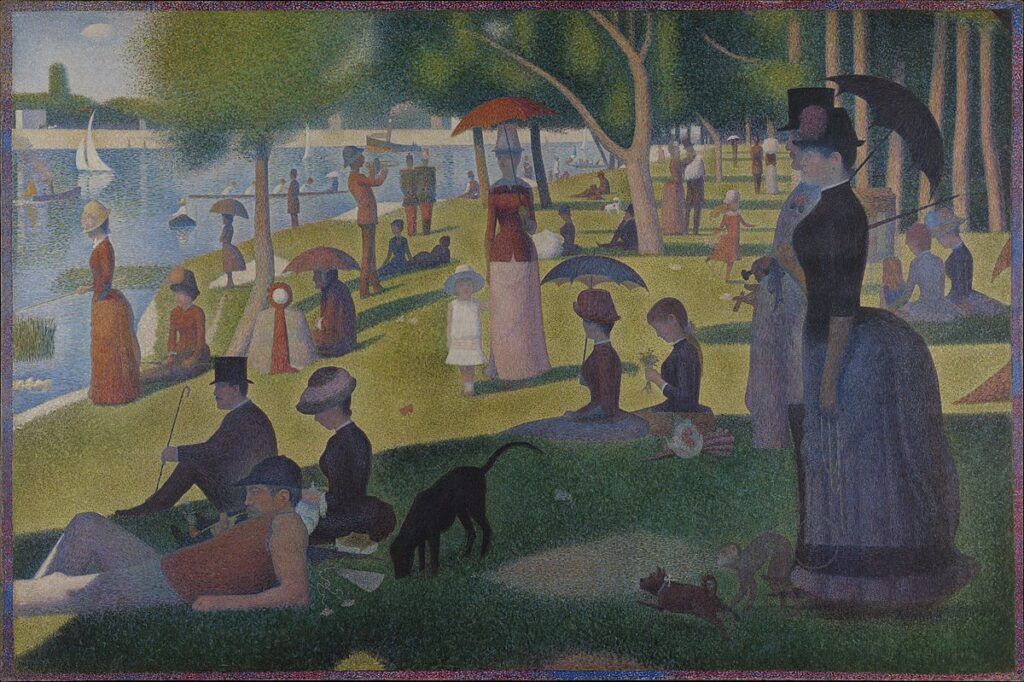

- Pointillism: Dots of paint creating images, pioneered by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac.

- Fauvism: Wild colors and expressive brushstrokes, led by Henri Matisse and André Derain.

- Expressionism: Focus on emotional perspective, exemplified by Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

- Cubism: Abstracted geometric forms, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

- Futurism: Captures speed and modern life; notable works include Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space.

- Dada: Anti-art, often satirical and absurd, epitomized by Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain.

- Suprematism: Abstract geometric shapes, led by Kazimir Malevich (Black Square).

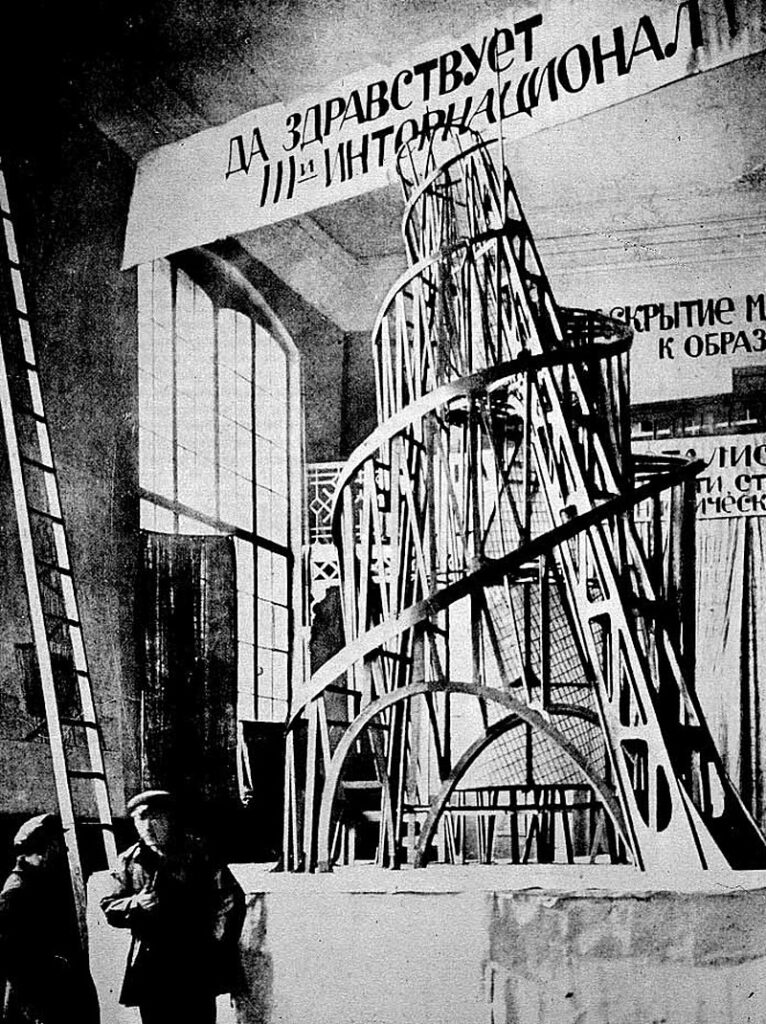

- Constructivism: Functional, industrial design-focused art, such as Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International.

- Mid-Century Movements:

- Abstract Expressionism: Emotionally intense, gestural art, championed by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko.

- Color Field Painting: Large, flat areas of color with emotional resonance (e.g., Rothko’s Number 13).

- Hard-Edge Painting: Defined shapes with sharp transitions, pioneered by Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella.

- Lyrical Abstraction: Emotive, painterly abstraction, popularized by Helen Frankenthaler.

- Optical Art (Op Art):

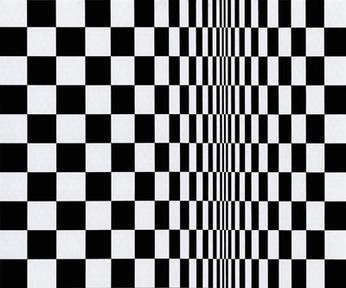

- Abstract art using optical illusions, such as Bridget Riley’s Movement in Squares.

- Key Artists:

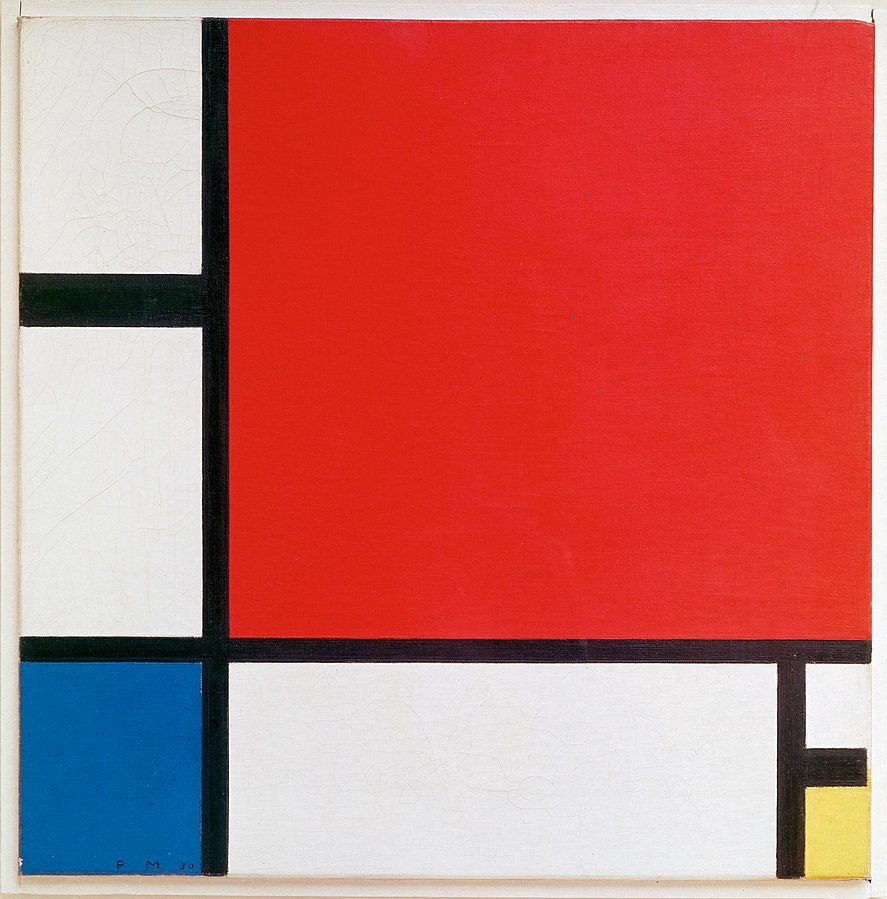

- Jackson Pollock (Number 1A, 1948), Piet Mondrian (Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow), Helen Frankenthaler (Mountains and Sea), Kazimir Malevich (Suprematist Composition), and Bridget Riley (Shadow Play).

1. Pointillism

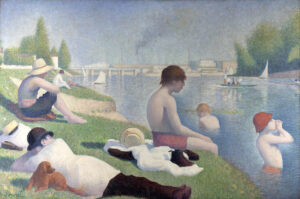

Perhaps the first version of abstract art was Pointillism. Pointillism grew out of Impressionism and is usually discussed as part of Neo-impressionism. It was founded in 1886 by the French painter Georges Seurat (1859-1891). Seurat was academically trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in the style of realism. However, in the mid 1880’s he began to diverge from the traditional path.

Seurat’s oil on canvas A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886) is perhaps the most well-known example of the Pointillist style. Art critics initially referred to Seurat’s dotted canvas as pointillist with a negative connotation. However, the term stuck and eventually lost its prejudice.

Pointillism developed concurrently with divisionism. Divisionism, or Chromoluminarisim, was a type of Neo-Impressionist painting that separated colors into dots or patches, which optically combined when the viewer stepped away from the canvas. Seurat was influenced by the critic Charles Blanc’s (1813-1882), Grammaire des arts du dessin (1867), which discussed color theory and vision in scientific terms.

Both movements took into account the scientific discoveries of color theory. Scientists such as Michel Euguene Chevreul (1786-1889) or Ogden Rood (1831-1902) worked on color theory. Chevreul contributed the idea of simultaneous contrast to color theory, which stated that the perception of colors changes based on the colors that are next to them. Unlike Divisionism, Pointillism focused on use of dots of paint not necessarily the separation of paint.

Another artist who worked in both the Pointillism and Divisionism style was the French artist Paul Signac (1863-1935). Signac’s L’Hirondelle Steamer on the Seine (1901) is more Pointillist, while his Portrait of Felix Fénéon (1890) shows a preoccupation with the idea of simultaneous contrast.

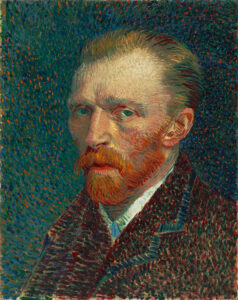

Other well-known works in the Pointillist style include French Neo-Impressionist Henri Cross’s L’air du Soir (1893), French painter Maximilien Luce’s Morning, Interior (1890), and Camille Pissarro’s La Récolte des pommes (1888). Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) used derivatives of Pointillism. Van Gogh’s Self Portrait (1887) features dots of paint side by side but retains some of the traditional practice of line drawing.

Though the works of Seurat, Signac, Luce, van Rysselberghe, Cross, Pissarro and Van Gogh are representational they are distorted, and the focus is on the combination of colors and brushstrokes in a scientific way. The use of the Pointillist style waned in the 1920’s as trends became more abstracted.

2. Fauvism

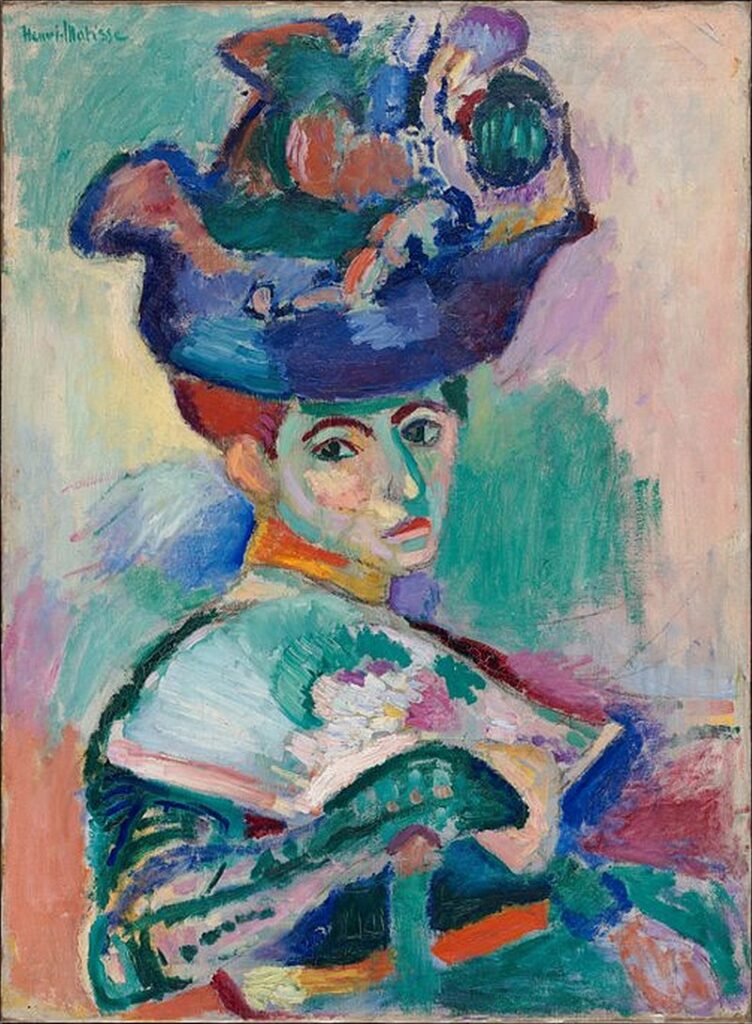

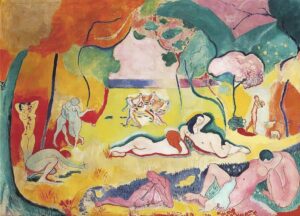

Fauvism was an early 20th century movement founded by a group of artists called Les Fauves. The movement was short lived, only ranging from 1904-1910. Les Fauves only had three exhibitions. At the Salon d’Automne of 1905 in Paris, French painter Henri Matisse (1869-1954) exhibited his Woman with a Hat. The art critic Louis Vauxcelles came up with the term Les Fauves to describe the artists like Matisse that were exhibiting in that style. Vauxcelles called them this because of the vivid coloration and wild brushstrokes they assaulted upon their canvases. In French, the term Les Fauves translates to mean wild beasts.

While Les Fauves were focused on how the artists saw the world around them, they were more concerned with strong blocky colors and painterly qualities over realistic representation. Fauvism is characterized by simplified compositions, abstracted subject matter, thick brushstrokes, bursts of intense colors and geometric shapes.

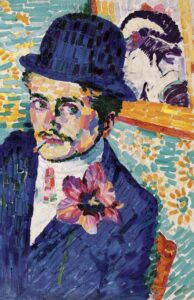

In addition to Matisse, other important members of the movement included Andre Derain (1880-1954) Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958) and Robert Delaunay. Derain’s Charing Cross Bridge, London (1906) shows an Example of a Fauvist landscape with its vivid unrealistic colors. This was exhibited at the Salon des independents 1906. Delaunay’s l’homme a la tulipe (Portrait de Jean Metzinger) (1906) was exhibited at the Salon d’Automne (1906) after which Les Fauves disbanded.

Initial inspirations for the Fauvists were Post-impressionism and Pointillism. Les Fauves were freed from artistic tradition. Matisse’s Le bonheur de vivre (1905-6) shares similarities with Paul Gauguin’s (1848-1903) Tahitian images. For instance, the saturated colors and perspective used to create the works is similar. The Fauvists also took inspiration from Gustauv Moureu (1826-1898) a teacher at Ecole des Beaux Arts and symbolist painter in 1890.

Cubism and Expressionism were artistic movements which developed around the same time. Georges Braque (1882-1963) would eventually work with Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) to hone cubism. In a similar vein, Cubism, would last only a few years but grew out of the freedom afforded artists after the break from artistic tradition. Fauvism was also instrumental in the development of 20th century abstraction.

3. Expressionism

Another one of the types of abstract art which was an offshoot of the post-Impressionist movement was Expressionism. Expressionism originated as a Northern European movement which affected art, music, dance, literature, theatre and poetry. Expressionism was particularly popular in Germany during the Weimar Republic (1919-1933). As an artistic movement, Expressionism took place during the first years of the 20th century and up to the First World War. Critics noted that Expressionism was a reaction against the positivist approach that had been particularly embodied by the Impressionists. In other words, as the Impressionists painted quaint scenes of the world around them, the Expressionists often represented the darker side of the world as it changed with the advent of technology.

Typically considered the instigator of Expressionism, Edvard Munch painted the Scream in 1893. The invention of photography had led artists to question what art could be if it didn’t need to represent reality. Expressionists were interested in the subjective perspective of the individual artist and saw the psychological and dramatic potential of the canvas. Munch distorted the painting to match his mood and to reflect an emotional experience rather than the physical reality. Rather than realistically depict the bridge, Munch depicted an emotional, almost nightmarish event, that was close to his own reality but far from visible reality.

A specific offshoot of Expressionism, which developed in Germany, was known as German Expressionism. This type of Expressionism popularized vivid, angular brushstrokes in bold color contrasts with a crude finish. Influences on Expressionism included Cubism, Fauvism, African and Oceanic art, Slavic folk art, as well as Medieval German art.

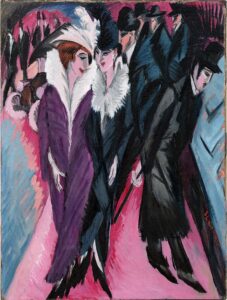

There were two main groups of the German Expressionists. They were The Bridge (Die Brucke) and The Blue Rider group (Der Blaue Reiter). Die Brucke first exhibited as a group in 1905 and was led by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938) and consisted of his fellow students from architecture school, such as Emil Nolde (1867-1956). The urban environment bustling with energy was a popular subject for Kirchner. For instance, Kirchner’s Street, Berlin (1913) features a couple walking a street in Berlin. Other members of Die Brucke included Fritz Bleyl (1880-1966), Erich Heckel (1883-1970), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1976), Otto Mueller (1874-1930) and Max Pechstein (1881-1955).

The Russian Born, Munich based painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) led the Blue Rider group, called such after Kandinsky’s image Der Blaue Reiter of 1903. Kandinsky believed that each brushstroke should be “an exact replica of some inner emotion.” Though his earlier works like, Blue Mountain (1908-1909) contained representational forms in vivid un-realistic color, his later abstract paintings like Composition VIII (1913) contained very little representational forms.

Kandinsky created, through his paintings, a visual language, in which he drew from musical composition. His expressionist canvases were eventually devoid of representational forms and only contained colors and shapes that referenced emotions of vaguely represented things of the world. His 1923 canvas Composition 8, at the Guggenheim Museum, is a good example of a work that relies on a spiritual feeling. Another member of the Blue Rider group was Franz Marc (1880-1916).

4. Cubism

Another highly influential movement of the early 20th century was Cubism. Developed between 1908-1914 by the Spanish Pablo Picasso alongside French artist Georges Braque, Cubism was inspired by the work of Paul Gauguin and Paul Cezanne. The Impressionists had developed the use of different points of view and the post-Impressionists utilized flattened picture planes. Cezanne began breaking up his canvas into “multifaceted areas of paint.”

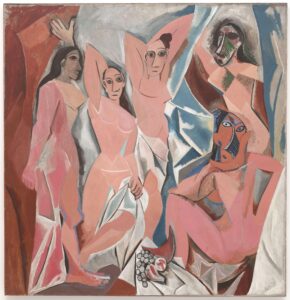

At a time when Picasso was living in Paris, inspired by these works, he painted Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907). This canvas represented five women built up of angular body parts and African mask inspired faces. The figures were merged into the ground and depicted from a multitude of perspective viewpoints.

Most scholars list Les Demoiselles D’Avignon as the first Cubist painting but note that is does not display the full development of Cubist style. Though Cubism is typically thought to have been invented by Picasso, it was Braque who honed the style.

Also responding to the views of Cezanne, Braque painted Houses at L’Estaque (1908). When viewing it, Matisse referred to Houses at L’Estaque as a bunch of little cubes and therefore developed the name for the movement, Cubism. Braque began to break up his canvas into cubes. The cubist style eventually developed into fractured angular figures and triangular shapes that displayed a multitude of viewpoints or perspectives. The Portuguese (1911) represents the peak of Cubism. In the oil on canvas the man sitting at café strumming a guitar exists in a shallow space.

Others working in the Cubist style include the Spanish Juan Gris (1887-1927), who followed Picasso, first painting in analytical Cubism, then moving to Synthetic Cubism before settling on Crystal Cubism. The first, Analytical Cubism was the traditional format of breaking down a scene and reassembling it in parts. Synthetic Cubism saw the buildup of scenes through a collage like format with materials other than paint, such as paper. During the Crystal period of Cubism, artists favored geometrically abstracted backgrounds, overlapping geometric planes and a flat compositional plane. Guitar and Pipe, (1913) is an example of Gris’s work.

Cubist artists took from the Fauves and the Expressionists the desire to express themselves in a different form of art but were more methodical than their counterparts. Cubist artists reconstructed their scenes based on geometric abstraction of what they saw and departed from Expressionism in their treatment of colors. In Cubism, color was secondary to structure and spatial design, leading the Cubists to utilize dull colors, like beiges.

Cubism, like so many of the abstract movements, developed in other artistic mediums. For his Guitar of 1912-1913, Picasso took cubist principles and applied it to the 3D medium of sculpture. In doing so, Picasso inspired an evolution of sculpture, that is the development of constructed, rather than carved or molded, sculpture.

Cubism was imperative for the development of 20th century abstraction, inspiring the development of Orphism, Purism, Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism, Vorticism, and De Stjil.

5. Futurism

Influenced by Cubism, Futurism mostly developed in Italy as a reaction to technology. Futurists attempted to capture speed and movement which was developing at an unprecedented rate due to technological developments. Futurism was a movement that celebrated movement and sought to capture it in abstracted forms. Futurism began shortly before WWI and went on to inspire creators across disciplines as well as inspire the development of Constructivism, Surrealism, Precisionism, Rayonism, Vorticism, and of course the Dada movement.

The Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) coined the term Futurism in his “Initial Manifesto of Futurism.” The manifesto was first published in 1909 in Milan in La Gazzetta dell’Emilia and later reproduced in the popular French newspaper Le Figaro. Marinetti laid out the notion that the younger artists, poets and composers wanted no part of the past and tradition of art. They were interested in youth, speed, technology and the triumph of humanity over nature.

In painting and sculpture, artists attempted to represent the speed of modern life. Their canvases and sculptures were charged with dynamic energy and represented movement. The Italian painter and sculptor Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916) is typically cited as one of the principal figures of the movement. Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), is a unique sculpture which attempts to represent a figure walking in Realtime.

Another Italian painter Giacomo Balla (1871-1958) attempted to capture movement on a canvas in 2D with his Abstract Speed – The Car has Passed (1913). This painting attempted to capture, abstractly, the wind as it rushed by when a car passed going 35 miles per hour, which was extremely fast to people then.

Other great artists included Carlo Carra (1881-1966), Fortunato Depero (1892-1960), Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979), Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), Gino Severini (1883-1966) and Luigi Russolo (1885-1947).

Sonia Delaunay painted Bal Bullier in 1913. Her colorful abstracted canvas represented couples moving on the dance floor of a Paris nightclub. Delaunay and her husband Robert were the founders of the simultaneous Orphism movement, which combined Cubism with the bright colors of Fauvism.

Marcel Duchamp chose to highlight form over color and made cubist stylistic choices in his Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2 (1912). This seminal work was met with negative reviews when it was shown, first at the 1912 Exposition of Cubism in Barcelona and later at the 1913 New York Armory Show. Initially described as an “explosion in a shingle factory,” this canvas displayed the preoccupation with capturing movement. Duchamp would go on to champion the French led Dada movement as a reaction against WWI.

6. Dada

Dada was an artistic movement which began in Zurich, Switzerland and lasted from 1915 until the middle of the 1920s. The Dadaists were responding to the horrors of WWI, by creating spontaneous and playful works which bordered on satirical. These artists felt that they could change the collective mindset and make others aware of the absurdity of the destruction of war. In fact, some noted that “art is dead” because they saw it useless to create beautiful things in the midst of a world that was destroying itself.

The term for the movement, Dada, was seemingly chosen at random, but conveys the shock, awe and irrationality that the Dadaists championed. Dada artists did not rely on previously establish artistic tradition, but instead sought to shock Europeans with their spontaneous pieces.

One of the well-known of the group, Marcel Duchamp shocked European audiences when he took one of the most revered paintings of all time, Leonardo Da Vinci’s (1452-1519) Mona Lisa and drew a mustache on a reproduction. Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. of 1919 was titled in this way because when pronouncing the letters in French it sounds like a vulgar saying which further demeans the Mona Lisa. This he called “assisted readymade” as he used a cheap postcard as the found object which started formed the backbone of the piece. In fact, Duchamp and the other Dadaists were uniquely concerned with what they called the found object. One of the most famous readymade pieces made the found object is Duchamp’s The Fountain of 1917, which is made from a urinal.

The American May Ray (1890-1976) was friends with Duchamp and assembled works from paintings, photographs and found objects. For his sculpture, The Gift, Ray purchased these random items in a Paris houseware shop and assembled them together. In a similar vein, Austrian Raoul Hausmann (1886-1971) used found objects to create his sculpture, The Spirit of Our Time (1919).

Another avenue of Dada was the photomontage. Hannah Hoch (1889-1978) created her image The Multi-Millionaire in 1923. The unique mixture of the cubist collage style done in photomontage created a unique visual image which commented on the relationship between man and the objects he produced.

Dada art was supposed to be anti-aesthetic. However, ironically Dadaists created a new aesthetic that endured throughout the rest of the century.

7. Suprematism

In Russia, the new form of Cubism was branded as Suprematism by the Polish-Ukrainian artist Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935). Malevich initiated the movement at the last Futurist Exhibition in St. Petersburg. During the 1915 exhibition, Malevich and others exhibited works in the Suprematist style which was a simplified version of Cubism typically featuring flat irregular rectangles on a pure background.

Suprematism operated under the notion that art didn’t need a subject matter. Instead, the important aspect was a supremacy of shape and color developed through pure artistic feeling. Malevich himself started creating works in a cubist framework. His early pieces combined an influence of Cubism, Futurism and the Blue Rider group. Malevich created a “grammar” of the Suprematist language, which was essentially shapes typically black circles and squares on a white background. However, he also used white on white.

Malevich’s Suprematist Composition (1916) was influenced by Futurism as it represented an airplane abstractly and attempted to capture a sense of flying. However, it was uniquely Suprematist due to the shapes, simplified color and abstraction.

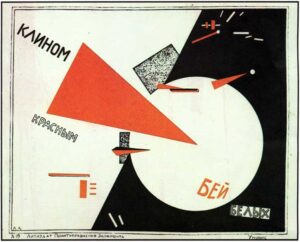

Another Russian artist, El Lissitzky (1890-1941) worked in the Suprematist style between 1919-1923. Other visionaries working with Suprematism included Ilya Chashnik (1902-1929), Alexandra Exter (1882-1949), Lyubov Popova (1889-1924), Sergei Senkin (1894-1963), and the artist and architect Lazar Khidekel (1904-1986).

This group created Suprematist abstract works, but many of them shifted to Constructivsim during the Russian Revolution from 1917-1923. In fact, Malevich produced a journal, Supremus to disseminate the Suprematist ideas. However, due to the Russian Revolution it was never released.

Although developed closely with Constructivism, Suprematism was diametrically opposed to its cousin. The Suprematist idea separated art and object meaning that art could not serve the state or religion. Suprematists were anti-utilitarian and fought for no objectivity to their works. Constructivism, on the other hand, focused on the object and how it could serve a utilitarian purpose.

8. Constructivism

The artistic movement, Constructivism, began in Russia around 1915 with two Russian artist- engineers concerned with how an artistic object could be used functionally. These two artists were Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) and Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956). Rodchenko created short video sequences, 3D art and photomontages in the Constructivist style.

Constructivism was initially inspired by the nonrepresentational objects in Malevich’s Suprematism. The term Constructivism came from their preference to construct planar and linear forms that suggested a dynamic quality and included moving parts.

This signaled a different type of sculpture than had been traditional. Rather than being molded or carved, Constructivist sculpture was being put together or “constructed” from unique materials such as plastic and electroplated metal.

One example of Constructivist sculpture is Tatlin’s Model for Monument to the Third International (1919). This sculpture, usually called Tatlin’s Tower, was created out of steel and glass. It rotated daily at various speeds and commented on the evolution of humanity to the highest state, which Tatlin believed to be the Communist state. Additionally, Tatlin had been concerned with space as the primary focus of the tower, rather than mass, as had been artistic tradition.

Suprematist shapes were used to carry out political functions. El Lissitzky, whose early work fell into the Suprematist category, later created works like Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919). For this, Lissitzky combined the Suprematist visual language with his political affiliations to create this piece of Bolshevik propaganda.

Both Suprematism and Constructivism influenced all areas of life. These movements influenced De Stijl and the development of abstract art in the modern world.

Constructivism gained popularity at the Bauhaus, a German art school that functioned between 1919 and 1933 and produced some of the most important names in European Abstract Art. When the Bauhaus closed in 1933 many of the artists came to the United States. An example were the artists Josef Albers (1888-1976) and his wife Anni Albers (1889-1994) who first taught at the Bauhaus and were instrumental at the Black Mountain College in Ashville, North Carolina.

9. Geometric abstraction

Geometric abstraction was the first of two district abstract art styles and featured both representational objects and a mix on non-representational shapes, geometric forms and colors. It focuses on the art itself rather than outside expression. Thus, it is opposite to abstract expressionism. In a sense, the term covers several artistic movements that became popular in the 20th century. Some of the proponents of geometric abstraction were Wassily Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevich (1879-1935), and Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). Two forms of geometric abstract art that were popular were De Stijl and Concrete art.

10. De Stijl

The Dutch Art Movement called De Stijl was founded in 1917 was known concurrently as De Stijl or Neoplasticism. This movement founded in Holland, advocated for the use of basic forms, most specifically rectangles, horizontals and verticals. Artists of the De Stijl movement also only worked in black, white or primary colors. By simplifying their visual vocabulary, they created a streamlined “language” of art.

One of the most well-known De Stijl artists was Piet Mondrian. Mondrian abandoned personal expression and objectivity within his painting. He simplified the language of painting down to straight lines, primary colors and rectangular shapes. The four elements; line, color, shape and space, he thought were part of a universal language that would promote universal harmony in painting. His rationally designed compositions, or tableaus, utilized only white, black and the three primary colors, Red, Yellow and Blue. For instance, Mondrian’s abstract painting Composition II in Red, Blue and Yellow (1930) used only those colors and only horizontal and vertical lines to create rectangles and squares. Dutch painter and critic Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) also painted in the De Stijl style.

The term De Stijl typically refers to art created in this fashion, in the Netherlands between 1917-1931. This De Stijl style bled into painting, architecture, furniture and graphic design in the Netherlands. In architecture, Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964) used these simplified shapes and pure visual language popularized by Mondrian to create the Schroder House in Utrecht (1924). Rietveld also used the primary colors and simplified lines in his created furniture like Red and Blue Chair (1923).

When the style influenced artists internationally it became known as the international style. For instance, American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) was concerned with a similar style as Rietveld and sought to create a distinct contrast between his constructed buildings and the natural world. Another architect working in the style was Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) who is most known for his German Pavilion (1929).

10. Concrete art

During the 1930’s in France, abstract artists was typically separated into two categories. Those that took an expressive approach and those that thought there shouldn’t be anything outside of the art itself. Critics began to refer to this second type of abstraction as cold abstraction and expressionism as warm abstraction. In a similar fashion to the artist of the De Stijl movement, artists of the Concrete Art moment favored art that was simple and unadorned with a unified purpose.

Concreate art was a term coined by Theo van Doesburg in the 1930s. Van Doesburg believed that abstract art should feature simple, unadorned structures and should abandon subjectivity. Van Doesburg’s ideal art was made up of impersonal elements like lines and colors rather than pictorial references which would need knowledge outside of the image.

Van Doesburg founded a group united under this banner called Art Concret. Art Concret only exhibited together a hand-full of times, in 1930, prior to Van Doesburg’s death. Art Concret championed geometric art that was fully abstract. Some members of Art Concret were Otto G. Carlsund (1897-1948), Leon Tutundijan (1905-1968) and Jean Helion (1904-1987).

In 1930, Art Concret published a manifesto in a magazine titled Revue Art Concret. This manifesto contained what they suggested were the basic rules of concrete painting. The artists of the group believed art should be universal. In other words, no outside knowledge should be required in order to understand the work of art. They eschewed symbolism and drama and did not want their works to contain any meaning outside of the work itself. In this way they were against impressionistic tendencies and thought painting should be mechanic.

However, Van Doesburg excluded artists whose work was not fully abstract. These excluded artists, along with defacto leader Joaquin Torres-Garcia (1874-1949), formed the group Cercle et Carre. Belgian critic Michel Seuphor (1901-1999) was a part of Cercle et Carre. This group held similarities with Art Concret, but allowed for expressive or representative tendencies to be present in the works of art.

Though Van Doesburg was the academic force behind the Art Concret movement, the term itself was popularized by the work of Max Bill (1908-1944) the Swiss architect and artist. An example of a public sculpture by Bill is Endlose Treppe (Endless Stairs) in Ludwigshafen. The sculpture consists solely of blocks atop each other and overlaid on top of one another. It is straightforward with no drama, outside meaning or didactical message. Therefore, it exemplifies the Concrete Art Movement.

11. Abstract expressionism

The other of the major abstract art styles was Abstract Expressionism or Post-Painterly Abstraction. In this art movement artists sought to use abstract art to express their emotions. Especially, this was the case in the years following World War II as artists tried to grapple with the horrors they had seen. This term served as a vague umbrella term for artists combining expressionism with abstract art. These artists took the expressive tendencies of artists like Van Gogh, and Gauguin and combined with the principles of abstraction. They built on the German Expressionism movement. The Ab Ex movement began in New York City in the 1940’s and is typically cited as the cause for the movement of the art world center from Paris to New York.

The abstract expressionist painted from a place of emotional intensity all while eliminating the figure from the canvas. Individual artists drew on their own emotional experiences to create Ab ex works. Examples of these artists were Clyfford Still, Willem de Kooning (1904-1997), Arshile Gorky (1904-1948), Mark Rothko, Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell (1915-1991), Franz Kline (1910-1962), Adolph Gottlieb (1903-1974), David Smith (1906-1965), Hans Hoffmann (1880-1966) and Joan Mitchell (1925-1992).

The pioneer of drip painting and a leading force behind this style of abstraction was American artist Jackson Pollock. To create his monumental canvases, Pollock lay them flat onto a floor and dripped, threw and flung paint at the canvas. In creating Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950) Pollock used sweeping gestures, dancing movements and violent swinging to merge the paint with the canvas. In doing so, Pollock believed he was becoming part of the painting both physically and psychologically. Pollock had studied Carl Jung’s notion of the unconscious and believed the theoretical arguments of unconscious expression in art. Pollock’s wife Lee Krasner has recently found fame for her own artistic practice in which she studied de Kooning’s work as well as developing her own uniquely feminine works in the abstract expressionist style.

Some more specific artistic movements were inspired by and are typically described as having existed under the umbrella of this movement. Some of these are Action painting, color field, Lyrical, Art informal, and Tachisme.

12. Lyrical Abstraction

Lyrical abstraction is a term that refers to a specific trend in art that occurred in the post-World War II period. The lyrical style was opposed to cubism, surrealism minimalism and the whole geometric abstraction. The term referred to a style of painting that was referred to as lyrical because it was painterly. This style is typically qualified as works with looser paint, illusionistic spaces. Some of the art styles and techniques that were used to create lyrical abstract pieces included looser paint, acrylic staining and drip painting. For instance, Rothko used staining and Pollock used drip painting. In this form of art paintings could be read as literal things themselves not representations of other forms. Artists in this style worked to create sensuous, romantic and loosely gestural works in a lyrical, or painterly, style.

Arshile Gorky (1904-1948) had used the term Lyrical to describe his abstract work since the 1940s. The term first came into major use in the art world March of 1951 when Michel Tapie (1909-1987) organized a show called Vehemences Confrontees at the Nina Dausset Gallery. The show featured both French and American artists. Tapie noted, when discussing the show, that “Lyrical abstraction [was] born.” However, in modern use the term has been considered controversial due it its tendency to simplify many very different styles of painting under one directive.

It became popular to refer to artists working in the lyrical style in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC during the 1960s-70s, when the term and style gained popularity again for a short period as some artists pushed back against minimalist art by arguing for a painterly approach to abstraction. The same thing happened in 1970 in Europe, when artists like Paul Kallos (1928-2001), Georges Romathier (1927-2017) and Thibaut de Reimpre (b.1949) led a revival of this art movement.

For artists in Europe, it was known as Abstraction Lyrique. Abstraction Lyrique artists included Jean Jose Marchard (1920-2011) who worked in a Tachisme style, Hans Hartung and Georges Mathieu (1921-2012). Other European artists whose works bordered on lyrical were Wassily Kandinksy, Serge Poliakoff, Pierre Soulages, and Jean Messagier. In fact, many American artists had lived and worked in Europe during the 1940s such as Sam Francis, Jules Olitski, Joan Mitchell. To this point, art critics suggested that the term and usage of European Abstraction Lyrique was an attempt to bring the center of the art world back to Paris, after its brief stint in New York City.

American artists pushed back, working hard in NYC and Washington D.C. to bring Lyrical Abstraction to life. These artists were Walter Darby Bannard (1934-2016), Ronald Davis (b1937), Helen Frankenthaler, Cleve Gray (1918-2004), Ronnie Landfield (b.1947), Robert Natkin (1930-2010), and Dorothy Gillespie (1920-2012). However, the new realism of artists like Yves Klein (1928-1962) would become the dominant style and inspire artists across the world.

13. Action painting

Action painting was a trend within abstract art during the 1940s to 1960s, which existed under the umbrella of Abstract Expressionism. It was inspired by and closely related to the New York school of expressionism as well as the French Tachisme. It was a trend within the Ab ex movement to create art that emphasized the physical act of painting over the finished product. This movement was a reaction to the horrors of WWII. Artists saw it as a way to express their inner emotions rather than portray recognizable objects.

Action based painting was pioneered by Jackson Pollock who utilized lots of gestural brushwork and spontaneously applied paint to his canvas. Pollocks works were devoid of narrative meaning, known symbols or signs. His monumental canvases explored his inner emotions. His Number 1A, 1948 is a perfect example of this type of art. The title contains no narrative context. Pollock believed that the mess on the canvas conveyed his inner self. Much of the development of this work was a performative act. Pollock placed the oversized canvas on the floor and threw, dropped and brushed paint onto the canvas in an aggressive and performative manner. In fact, he even cut one of the tubs open and squeezed the paint directly onto the canvas as well as including his own handprints.

Individual artists that created art through action are Sam Francis, Willem de Kooning, Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989), Michael Goldberg (1924-2007), Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan (1922-2008), Franz Kline, Joan Mitchell and Philip Guston (1913-1980).

The term for this trend had truly been defined by Harold Rosenberg. Rosenberg had suggested that the actual art was the action of making the work rather than the work itself. This notion was diametrically opposed to Clement Greenburg’s thought that art only becomes art when it is displayed as such. Rosenberg’s theory of art would influence the development of the following artistic movements; Fluxus, conceptual art, performance art, and instillation art.

14. Art Informel

Art Informel is the general term for an artistic movement that encompasses several unique trends in art including Lyrical based abstraction, Tachisme and art brut. The informal movement is the European version of Abstract Expressionism and was popular between 1940s and 1950s in France. It was a part of the non-geometric abstract art in this period meaning that it drew on non-representational art. Art Informal completely lacked any sort of formal qualities or pictorial tradition in painting and art. This movement allowed artists the freedom to explore their inner feelings.

Artists of this movement were no longer concerned with whether the art could be understood in the traditional since. They did not use recognizable objects, signs, symbols or traditional narrative markers. Instead, they created their own individual and private language to express themselves in art.

One artist of the movement was the Spanish born, but French resident Laurent Jimenez-Balaguer (1928-2015). Jimenez-Balaguer’s work was performative. He used gestural strokes and considered the painting of the canvas part of the art itself.

One sect of the movement were the artists working in Calligraphic Abstraction. This meant that they used elements of writing or writing like forms in their art. Artists known for this were Hans Hartung (1904-1989), Pierre Soulages (1919-2022) and Georges Mathieu (1921-2012). Artists working in the informal style of art included Sam Francis (1923-1994), Pablo Serrano (1908-1985), Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), and Jean Paul Riopelle (1923-2002).

Many of the artists numbered their canvases in order to remove all narrative elements. Hartung created this work, T1989-A4, in 1989 and utilized a Tachsime based staining technique and gestural brushwork to complete it. There was no denying how important this movement would be for the development of modern art.

15. Tachisme

A part of the Art Informal movement, Tachisme, was largely a reaction to the expressionism that was so popular at the turn of the century. After initiation in American, the abstract expressionist movement took on a less aggressive but equally as popular output in Europe in the 1940s and 1950s. In France, during this period, geometric abstraction was less popular, and artists were interested in expressing their inner feelings through abstraction.

Tachisme was inspired by Cubism and the lack of form in the Art Informal movement. Artists that worked in this style featured no objectivity but only feeling and expression played out on an abstract canvas.

Similar to the action-based painting made popular by Jackson Pollock in America, Tachisme featured spontaneous brushwork that happened in the moment. In this way, the artists had the freedom to splash, drip and plop blobs of paint onto the canvas in an organic and unhindered way.

The term Tachisme comes from the French word Tache which means to Stain and referred, of course, to the method of staining the canvas that was prevalent with artists like Jean Messagier (1920-1999), Serge Poliakoff (1900-1969) and Sam Francis (1923-1994).

Many artists worked in the Tachisme style including Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923-2002), Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985), Pierre Soulages (1919-2022), and Hans Hartung (1904-1989).

16. Color field

Color field painting was one of the abstract art movements and it focused on large areas of flat color that was unbroken on the picture plane. Artists had different ways to achieve the color field, or color blocking effect, including staining and spraying colors on the canvas. This term denoted a mid-century trend in that began in New York during the 1940s and 1950s as a rection to artists like Pollock. From New York, the style migrated to Washington D.C. where Kenneth Noland (1924-2010) and Morris Louis (1912-1962) took charge. Color Field became popular in Canada, Britain and Australia, as well. One abstract painting in the color field style is Beginning (1958) by Noland.

As the style continued in 1960’s artists who worked in Color Field began to move away from the extreme emotional output of Abstract Expressionism and Action painting and towards a more serene color blocking style. In Color Field, the color is the subject of the image rather than representing a secondary object.

One very well-known Color Field painter was American painter Mark Rothko (1903-1970). After being influenced by urban scenes and surrealism in the 1930s and 1940s, Rothko developed these nonfigurative works such as Number 13 (White, Red on Yellow), which is housed at the Metropolitan Museum in NYC. Rothko was inspired by Clyfford Still (1904-1980) who had used color to evoke moods in his Abstract Expressionist works.

Another American artist working in the Color Field style was Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011), whose famous Mountains and Sea (1952) features a newly pioneered staining technique which combined Pollock’s poured paint technique with Rothko’s fields of color.

Important Color Field painters included Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman (1905-1970) and Arshile Gorky. In fact, many of the artists who worked in the Color Field style began as Abstract Expressionists. Other creators that continued to work in the color field style included Sam Francis (1923-1994), Sam Gilliam (1933-2022), Gene Davis (b.1952), Jules Olitski (1922-2007) and Frank Stella (b. 1936). The emphasis on areas of color would continue even after the re-introduction of objects and figuration into postmodern art.

17. Hard-edge painting

In the 1950’s in the United States a specific type of abstract art was made popular. Closely related to Geometric abstraction and Color Field Art, Hard-Edge painting’s main characteristic was the abrupt transition between one shape and the next. The art form shared with Color Field the characteristics of large blocks of color. However, Color Field art also included looser brushwork and did not dictate that all edges needed to be hard and sharp.

In order to achieve the Hard-Edge look, artists used quick drying acrylic paint and uniform application as well as tape in order to make shapes and precise lines. In sculpture this resulted in a minimalism.

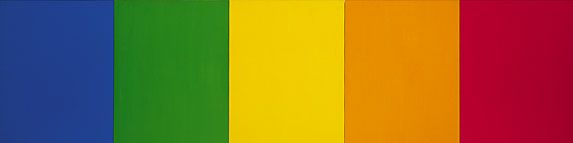

A good example of this is American painter Ellsworth Kelly’s (1923-2015) Blue, Green, Yellow, Orange, Red (1966). The five colors are divided precisely one after the other.

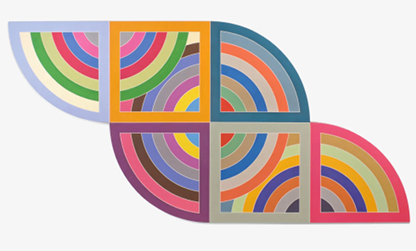

One of the concepts that dictated Color Field and Hard-Edge painting was that a painting was only a flat colored surface and didn’t carry any outside meaning. In fact, it was American artist Frank Stella (b.1936) who was quoted as saying that a painting was “a flat surface with paint on it-nothing more.” Stella’s Hard-Edge paintings are iconic in that his paintings combine Hard-Edge painting with minimalist sculpture. Examples are Harran II (1967) or Agbatana III (1968)

Other Hard-Edge artists included Karl Benjamin (1925-2012), Lorser Feitelson (1898-1978), Frederick Hammersley (1919-2009), June Harwoood (1933-2015), and Helen Lundeberg (1908-1999).

18. Op art

The term Op Art was first used in a 1964 article, about Polish artist Julian Stanczak’s (1928-2017) show Optical Paintings. The article was published in Time Magazine. The term was short for Optical Art. It refers to an art movement in the 1960s and 1970s in which abstract art was being produced in a way that involved optical illusions. Artworks were typically created by combining black and white shapes in a way that gave the impression that movement was occurring when it was not. As viewers approached these pieces they seemed to move, flash or warp or hidden images appeared from certain angles and not from others. Sometimes called, Trompe L’oeil, or “trick of the eye” in French, the illusionary affect was

Another form of abstract art, Optical art was influenced by Neo-Impressionism, Cubism, Futurism and Dada art. However, perhaps the most influential movement was constructivism which gained popularity in the Bauhaus.

Hungarian Victor Vasarely (1906-1997) is typically thought of as the European leader of the movement. Vasarely’s sculpture in Pecs shows how the tradition of illusions transitioned into sculpture. When viewed from the side, the sculpture is made up of small colored blocks on a flat surface. However, when viewed straight on two cubes seem to float within a 3D space due to the optical illusion.

William C. Seitz’s (1914-1974) exhibition The Responsive Eye (1965) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York brought fame to the movement in America. Other artists that worked in this art style include Isia Leviant (1914-2006), Julian Stanczak (1928-2017) and Richard Anuszkiewicz (1930-2020).

After some time, artists began producing optical illusions with color. One of those artists was Bridget Riley (b.1931). The British artist was known for Movement in Squares (1961) which was a typical example of a Black and White optical illusion which seemed to move as you look at it. However, Riley’s later work like Shadow Play (1990) incorporated colors.

Citations

- Brodskaya, Nathalia. The Fauves. United Kingdom: Parkstone International, 2012.

- Frank, Patrick, “Prebles’ ArtForms” Pearson Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River: New Jersey, 2009.

- “What does Pointillism Mean to Modern Art,” Youtube, Uploaded by Seens, 2021

- “Why is that important? Looking at Jackson Pollock,” Youtube, Uploaded by SmartHistory, 2010