Cubism emerged in France around 1907 and lasted until 1914. Cubist artwork typically features a fragmented composition representing the subject from all angles or overlapping geometric planes. Artists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque led Cubism through its phases: Proto-Cubism, Analytical Cubism, and Synthetic Cubism.

Expressionism emerged in Germany around the start of the 20th century and lasted from around 1905-1920. Expressionist painting typically presents the world from a subjective perspective, radically distorting subject matter for emotional effect to evoke intense emotions or ideas. Key Expressionist artists include Edvard Munch, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Egon Schiele, Wassily Kandinsky, and several others.

Cubism and Expressionism have many similarities, the three most significant being loose brushwork, distorted subject matter, and a rejection of academic painting conventions.

The three main differences between Cubism and Expressionism are the use of color, subjective interpretation, and the treatment of form.

Cubism and Expressionism Similarities

Cubism and Expressionism have many similarities, the three most significant being loose brushwork, distorted subject matter, and a rejection of academic painting conventions.

Cubism vs. Expressionism: Loose Brushstrokes

Cubism and Expressionism are among the first Western art movements to use thick, expressive brushstrokes. Both movements sought to remove themselves from the conventions of literal representation and embrace a more expressive style of painting, whether emotional like Expressionism or technical like Cubism.

Cubists reassembled their subjects using short, sketch-like brushstrokes to build up color and value in opaque layers. Loose brushstrokes could also suggest a variety of emotions, especially when paired with colors, making it an essential technique for many Expressionist painters.

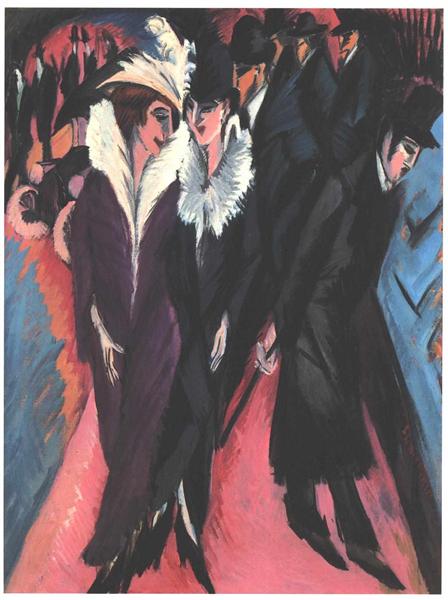

Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s painterly yet sharp brushstrokes convey a sense of tension in Street, Berlin, pictured below:

Cubism vs. Expressionism: Distorted Subject Matter

Cubism and Expressionism rejected the illusion of reality central to the Realism and Naturalism art movements. Instead, Cubism and Expressionism sought to reinterpret reality through a more playful and expressive lens. The loose brushwork, play on perspective, and bold color seen in Cubist and Expressionist artwork inevitably distorted their subject matter. Distortions were evident in portraits, still lives, and landscapes.

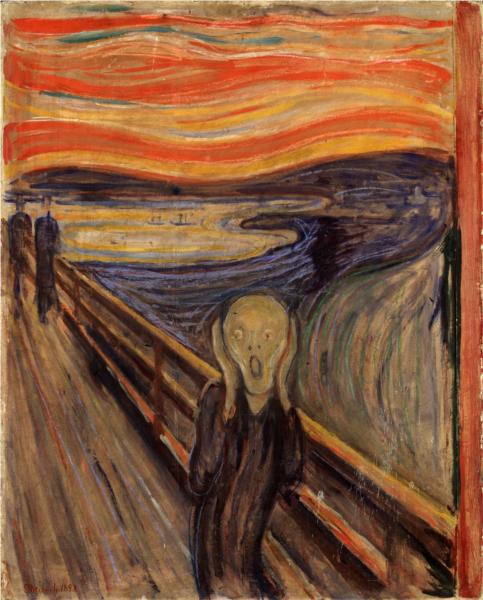

Expressionist Edvard Munch’s famous painting The Scream, pictured below, shows a figure whose face and hands are distorted, appearing long and languid, and without realistic definition:

Cubism vs. Expressionism: Rejection of the Academy

Expressionism distanced itself from art historical tradition by rejecting the reverence for genre painting upheld by European art academies. Expressionism did not idealize its subjects or place them in a hierarchy. Expressionist painters reinterpreted their subjects through their subjective lens.

Similarly, Cubist painters rejected tradition by painting fragmented compositions with overlapping planes rather than the linear perspective of the Renaissance. Cubists also avoided gradations of value and abandoned the illusion of depth altogether by developing the papier collé (pasted paper) technique.

Cubism and Expressionism Differences

The three critical differences between Cubism and Expressionism are the use of color, subjective interpretation, and how form is handled.

Cubism vs. Expressionism: Color

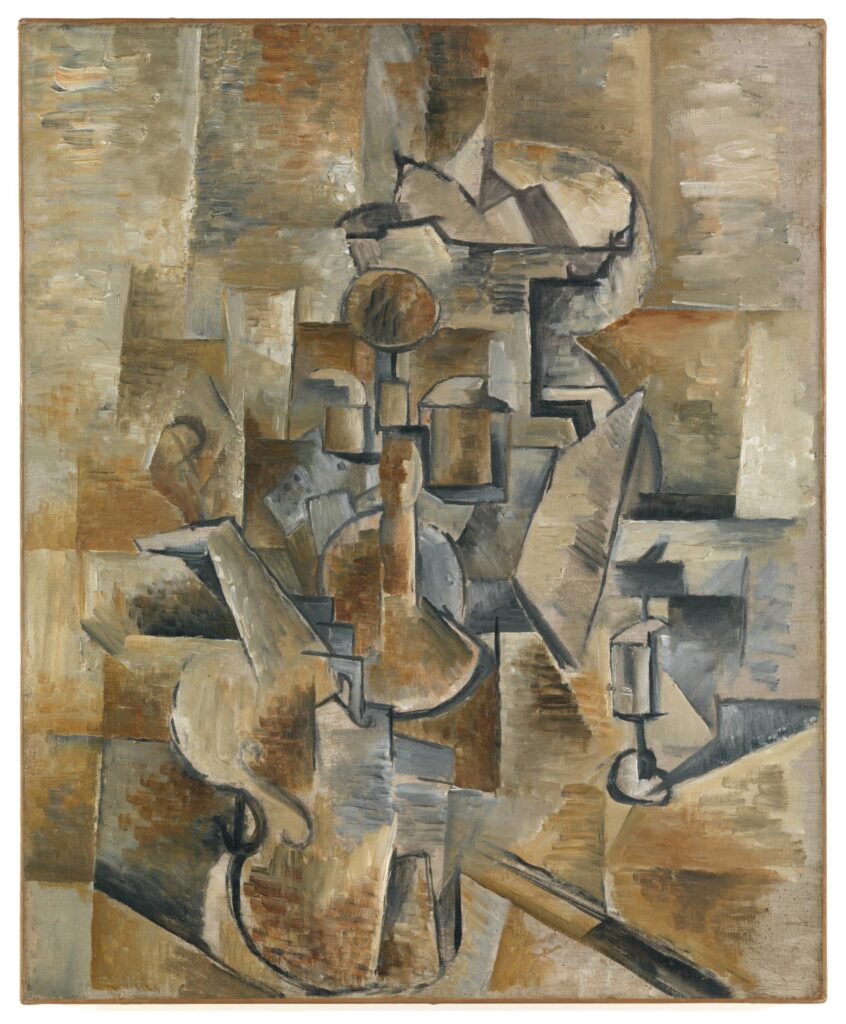

Cubist paintings, particularly those of the Analytic Cubism phase, display a monochromatic color palette with mainly dark, earthy tones. Cubists often used a monochromatic scale to keep the viewer focused on their subject matter’s avant-garde structure and form.

A limited palette of earthy tones is seen in George Braque’s Still Life (Violin and Candlestick), below:

On the other hand, Expressionist painters used color in alignment with the intense emotional states they wanted to convey. Expressionists used intense, non-naturalistic colors to achieve a sense of artistic and conceptual protest, a reaction to previous art movements and the troubling state of the world at the time.

Wassily Kandinsky’s Composition IV features a range of primary colors with darker accent lines connecting elements throughout the composition, seen below:

Cubism vs. Expressionism: Subjective Interpretation

Expressionist painters expressed a scene as it existed in their minds rather than how it appeared in reality. Expressionist artists used loose, rapid brushwork, distorted shapes, and bold color to express feelings such as angst, anxiety, and alienation.

Cubists were less concerned with subjective interpretation and focused primarily on reimagining reality through revolutionary stylistic changes, a reaction to modern art. Cubists experimented with alternative ways of representing a subject in space by rejecting the stylistic conventions of French academic painting.

Cubism vs. Expressionism: Form

Cubist and Expressionist paintings are highly recognizable because of how they reimagine form. Many Expressionist painters had experience in printmaking, which can render a stark, flat image that seemed almost two-dimensional.

Cubist paintings also demonstrate two-dimensionality but manipulate their subject matter to the point where a human subject’s once organically-shaped limbs are reassembled as a collection of cubes, cylinders, and cones.

What are other Art Movements Similar to Cubism and Expressionism?

Much like Cubism, Expressionism was influenced by the Fauvism art movement, which explains Expressionism’s tendency toward jarring compositions and bright, sometimes arbitrary, colors. The Cubist and Expressionist movements overlapped with numerous other art movements that emerged in the early 1900s, including Futurism and Dadaism.

Fauvism was a short-lived movement that emerged around 1905 and dissolved around 1908. Fauvism rejects Impressionism’s soft, pastel color palette and is characterized by bold, contrasting colors and loose brushstrokes. Fauvist paintings are figurative, meaning that the subject is recognizable but leans towards abstraction.