What is Fluxus?

Fluxus refers to an international avant garde art movement, popular in the 1960s and 1970s that valued chance, indeterminacy and the process of art-making over the final product. Fluxus artwork typically consisted of experimental art performances that were expressly anti-art and Fluxus artists sought to make all forms of art accessible to the masses by rejecting their institutional conventions. The Fluxus art movement embraced the collaboration of many art forms, including visual art, poetry, music and design.

Examples of Fluxus Art

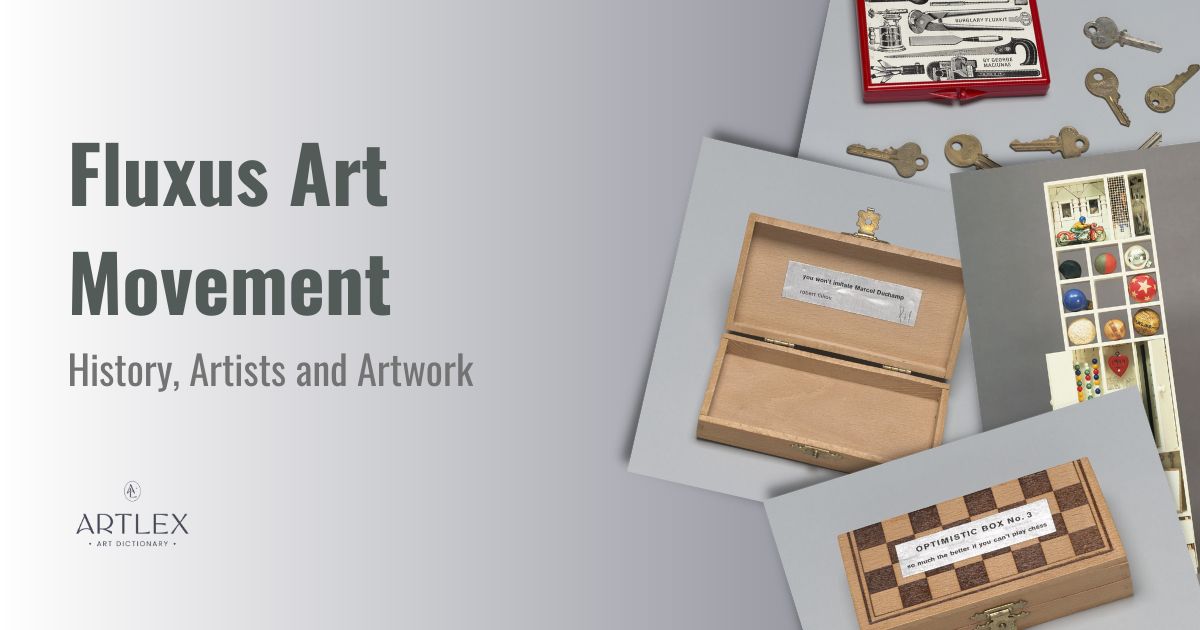

Optimistic Box #3 – So much the better if you can’t play chess (You won’t imitate Marcel Duchamp), Robert Filliou, 1969, Museum of Modern Art, New York

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/135457

Make a Salad, Alison Knowles, 1962 –

https://www.aknowles.com/salad.html

Repository, George Brecht, 1961, Museum of Modern Art, New York

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81283?sov_referrer=art_term&art_term_slug=fluxus

Burglary Flux Kit, George Maciunas, 1971, Museum of Modern Art, New York

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/127929?sov_referrer=art_term&art_term_slug=fluxus

Grapefruit, Yoko Ono, 1964, Museum of Modern Art, New York

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/128103

Defining Fluxus

Fluxus artists aimed to prolong the existing tradition of disrupting the art world in many ways. The most significant way that Fluxus defied conventions was that it did not intentionally result in an art object to be displayed in a museum. Instead, Fluxus works typically took the form of an event often facilitated by a short prompt or an unanticipated art object.

A Fluxus event accompanied by a prompt or set of instructions was called an event score. Event scores echoed the format of a musical score, blending the methods of the two art forms, musical composition and visual art, together to produce an immersive experience similar to that created by Performance artists.

While Fluxus shares technical and ideological similarities to Dadaism and Performance Art, it is difficult to define Fluxus using the same conventions as preceding art movements, as it did not have an overarching or unifying style of representation. Fluxus did not align with specific artistic media, such as painting or sculpture. Instead, Fluxus adhered to a philosophy that positioned art creation under Fluxus as an attitude rather than a movement. Fluxus works were meant to be simple, mixed media and fun. Like Dada, Fluxus was one of the earliest movements to embrace humor. Fluxus also favored certain materials and methods for the easy distribution of art and made use of existing societal structures, such as galleries and registered mail, to provide the public with easier access to the artwork.

The Fluxus movement was playful and turned everyday objects and actions into living art. In many instances, Fluxus artists sought to turn life itself into an ongoing act of art creation. Fluxus events were often random performances that welcomed chance occurrences and encouraged collaboration between artists and art forms. Audiences could also act as collaborators rather than merely spectators. In fact, the philosophy of Fluxus required the viewer to interact with the piece in order for it to be considered complete.

Key artists already working in the methods of Performance Art and Conceptual Art brought similar methods into Fluxus art throughout the 1960s. In 1962, American artist Alison Knowles organized the Fluxus event Make a Salad according to simple instructions: Make a salad. This prompt was part of a larger body of instructions, or scores, from the Great Bear Pamphlet Series, published in 1962. Alison Knowles used London’s ICA Gallery to stage the first of many live salad-making events where she prepared a larger-than-life salad to the beat of live music and served it to the audience. The Fluxus artist’s animated performance mirrored Fluxus ideals by turning the mundane act of preparing a salad into an exciting and humorous event, where anything could happen.

History of Fluxus

Fluxus was founded in 1960 by George Maciunas, a Lithuanian-American artist. George Maciunas was deeply inspired by the work of avant garde composer John Cage and his experimental musical compositions. With its anti-art spirit, Fluxus echoes earlier avant garde movements such as Dadaism and the anti-academic art of the Gutai group. Unlike previous art movements, Fluxus was seen as more of a shared attitude than an art movement. This is because Fluxus artists were collectively anti-art and prioritized the creation of a Fluxus experience rather than an art object. Pieces of physical art created by Fluxus artists were often just facilitators of the larger event.

John Cage’s Influence on the Fluxus Movement

From the 1930s through the 1960s, Composer John Cage explored experimental music influenced by his studies in Zen Buddhism. Cage later taught classes in experimental composition in New York City that explored how musical compositions could be performed in infinite ways. Cage’s experimental music classes attracted musicians, such as La Monte Young, visual artists, such as Nam June Paik, and poets, such as Robert Filiou, many of whom were already practicing in anti-art styles. Other artists eventually collaborated within the Fluxus network, denying any conventions associated with an official art movement. Fluxus works like George Brecht’s Drip Music from 1962 are among the performances directly associated with John Cage’s influence.

The Fluxus Manifesto

Fluxus ideals are evident in the name Fluxus, where Fluxus refers to that which is flowing out or in constant motion. According to Fluxus founder George Maciunas and the Fluxus Manifesto, the purpose of Fluxus was to:

“…purge the world of bourgeoisie sickness, ‘intellectual,’ professional and commercialized culture, purge the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art, mathematical art, purge the world of ‘Europanism!’ Promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, promote living art, anti-art, promote non art reality to be fully grasped by all peoples, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals…” [1].

While the Fluxus manifesto dictated the purpose of Fluxus, public events such as Fluxfests, the official name for a Fluxus festival, and Fluxus street theatre embodied the true spirit of Fluxus. Fluxus went on to embody the constant motion that the name itself implies by staging international events and ultimately forming an international network of Fluxus artists.

Fluxus’ international network of artists were primarily centered in major cities in New York, Japan and Germany. Fluxfests were organized across Western Europe and presented work by key artists George Brecht, Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, George Maciunas, Ben Vautier and Wolf Vostell.

Fluxus Kits and Fluxus Multiples

Fluxus boxes, also known as Fluxus kits or Fluxkits, were another way Fluxus artists aimed to embrace chance and defy high art standards. Fluxus boxes also aimed to make Fluxus art accessible to the masses and were typically composed of everyday objects, including playing cards, various forms of printed matter, keys and elastic bands gathered up within various containers including suitcases, toolkits and boxes.

Sometimes, Fluxus boxes included instructions for mail art or contained absolutely nothing apart from a cheeky bit of text, as is the case with Fluxus artist Robert Filliou’s Optimistic Box #3 from 1969. This box simply offers a supposedly optimistic take on playing chess against Dada founder and chess enthusiast Marcel Duchamp, reading “So much the better if you can’t play chess” on the exterior of the box and “You won’t imitate Marcel Duchamp” on its interior.

The intention behind Fluxus boxes and other multiples was that a box could find itself in the possession of any person and that person could activate the artwork by responding to its instructions. The prompts and instructions were often left intentionally vague so as to incite an entirely unpredictable outcome from the interaction.

The same was true of other Fluxus art, including artists’ books like Grapefruit by Yoko Ono, from 1964. From self-reflection to stillness and creation to destruction, Grapefruit calls the reader to engage with each of the prompts included in the book, such as to watch snow fall and make yourself a sandwich, along with its final invitation to burn the book after reading it. Fluxus multiples, though now revered as art objects, were meant as catalysts for chance and indeterminacy in ongoing acts of live art.

The Influence of Fluxus on Modern and Contemporary Art

Many Fluxus artists argue that the Fluxus movement did not end in 1978, with the death of Fluxus founder George Maciunas. This is because Fluxus is seen as less of a movement and more like a set of core values that live on through the activation of Fluxus’ philosophy. Many contemporary artists still incorporate humor, satire, and ephemeral materials that are inexpensive and utilitarian into their art.

Since Fluxus had no unifying style of representation, labelling contemporary artworks as Fluxus works within the context of the art world remains challenging, despite the advances in technology that make the prolongation of the Fluxus attitude all the more possible. The intermedia approach of Fluxus played an important role in influencing art movements throughout art history, including contemporary new media, video artworks and emerging forms of digital art.

References

[1] Maciunas, George. “Manifesto I.” George Maciunas Foundation Inc., 13 Feb. 2013, http://georgemaciunas.com/about/cv/manifesto-i/.Notable Fluxus Artists

- George Maciunas, -1978, Lithuanian-American

- John Cage, 1912-1992, American

- Robert Filliou, 1926-1987, French

- Nam June Paik, 1932-2006, Korean-American

- Yoko Ono, b. 1933, Japanese

- Alison Knowles, b. 1933, American

Related Terms

- Conceptual Art

- Performance Art

- Artists Books

- Avant Garde

- Pop Art

- Futurism

- Minimalist Art

- Performance Art