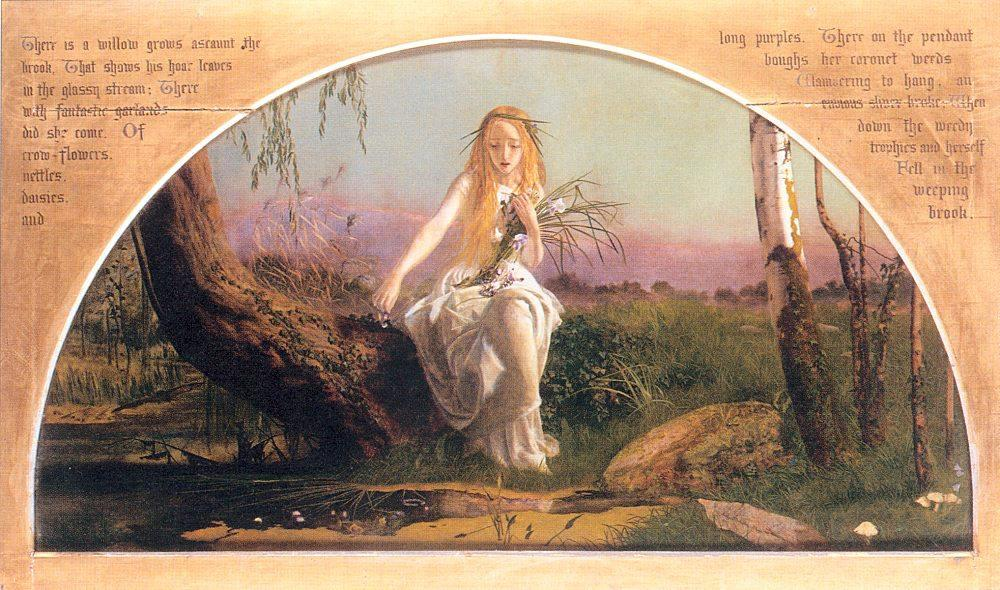

The painting featured here is titled Ophelia and might be the singularly most recognizable Pre-Raphaelite Painting. This oil on canvas was painted by the British artist Sir John Everett Millais between 1851 and 1852. The canvas measures 30 inches tall by 44 inches in width.

What is Depicted in the Artwork?

Like many of his contemporaries, Millais paintings often drew their narratives from literary sources. For his oil on canvas entitled Ophelia, (1851-1852), Millais chose the play Hamlet, by William Shakespeare (1564-1616). Ophelia was a protagonist from Hamlet. Ophelia’s lover Hamlet was killed by her father. Initially, Ophelia was stricken with grief after the death of her beloved Hamlet. She made a garland of wildflowers and sat on a willow tree. The branch broke and she fell, or perhaps jumped, into the water. This painting depicts Ophelia singing as she slips below the surface of the water.

In Act IV, Scene vii, of Hamlet, Queen Gertrude describes the scene in great detail. The scene is typically not depicted on stage, but plays out in the descriptive words of the Queen:

There, on the pendent boughs her coronet weeds

Clambering to hang, an envious sliver broke;

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And, mermaid-like, awhile they bore her up;

Which time she chanted snatches of old tunes,

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element; but long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pull’d the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.

In addition to depicting Rosetti’s wife, Siddal in the guise of Ophelia, Millais chose to render a landscape of Hogsmill River in Surrey. Over a five-month period, Millais dutifully studied the plants, animals and landscape of the chosen spot along the river. Like the other Pre-Raphaelite painters, Millais wanted to emphasize the natural world.

Images of Ophelia

Artwork Analysis

Millais took much from inspiration from Shakespeare’s description. Additionally, Millais wanted to recreate the atmosphere with accuracy and dedication to nature. Millais rendered the vegetation with extreme attention to detail. The plants and flowers can be identified because of their botanical accuracy. Ophelia’s garland of flowers, which she was creating prior to falling into the water, is present in Millais’s painting.

Also, the flowers Millais chose were representative of Shakespeare’s description of the garland from Hamlet. One of the flowers represented is the poppy, which in Victorian art and literature often represents death and sleep. Another flower Millais chose to display was the violet, which represents faithfulness, but also Chasity or the death of youth. Other flowers that contain symbolic meaning include the pansies for love in vain, the willow for forsaken love, and the daisy for innocence. In Hamlet, Ophelia’s brother Laertes refers to her as the “rose of May,” which might account for the inclusion of roses.

In addition to the accuracy, part of what made Ophelia so remarkable was the intensity of color that Millais was able to produce. Like other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Millais painted on a white wet ground causing the white to mix with the color. This provided a bright luminosity. The bright greens of the vegetation brighten the canvas in an unconventional way.

Upon Millais’s canvas we witness what Shakespeare described as a muddy death. The clear water is muddied with the brown silt that Ophelia has kicked up in the fairly shallow brook. Areas of bright green moss flank Ophelia’s widespread gown. True to Shakespeare’s description of the event, Ophelia’s dress is decorated with silver embroidery. Ophelia wears a dress with silver embroidery. In fact, we know from a letter written by Millais to Thomas Combe in 1852, that Millais actually owned this dress. Millas wrote, “Today I have purchased a really splendid lady’s ancient dress.” Millais actually purchased this gown for Elizabeth Siddal to wear while posing as Ophelia.

The color of Ophelia’s human flesh draws the viewers eye in. The grim shade was both macabre and startling to the Victorian viewer. Ophelia’s death was not typically depicted in painting, only vaguely alluded to. Surprisingly, Millais shows Ophelia at this moment with her mouth frozen in song as she drowns in the river. Ophelia’s hair floats, mermaid like in the water around her. This description once again comes from Shakespeare’s original work, showing Millais dedication to accurately representing the scene as textually described.

Overwhelmed by her grief, Ophelia lay in the water, singing songs. Ophelia is seemingly unaware that staying in the water will lead to her death. Ophelia’s arms are propped open, in helpless surrender, only her palms and fingers remain above water. The closely cropped scene and the lush habitat around Ophelia in the brook, create an unescapable scene of impending death.

Ophelia’s pallor can be attributed, in part, to the story of Elizabeth Siddal posing for the figure and how she caught a severe cold due to the cold water in the winter months. Millais posed Siddal in a bathtub full of water. Millais painted the central figure of Ophelia during the winter at his studio in London. Millais used oil lamps to heat the water. However, after such a long time, the water became ice cold. Siddal did not complain or ask to stop and eventually became very ill. Siddal’s father threatened Millais and sued him for the doctor’s bills.

For a period of time these lines, spoken by Gertrude, describing Ophelia’s death, were omitted from stage productions of Hamlet. There was a certain sexual connotation that came along with the line regarding her as a mermaid. This sexualization and the dirtying of the water and her death meant that Millais’s Ophelia, like Shakespeare’s original Ophelia, did not fit the Academy standards of innocence.

History of Ophelia

When painting, Ophelia, Millais likely chose this Shakespearian story to paint because it was a popular subject at the Academy. In July of 1851, Millais began painting outdoors at Ewell in Surrey, England. Millais had located a place along Hogsmill River that matched Shakespeare’s description of the scene in Hamlet. In an effort to fulfill the Pre-Raphaelite doctrine, Millais relentlessly studied the natural landscape. Millas spent up to 11 hours each day, 6 days a week for months, attempting to perfectly depict the landscape as he saw it.

Millais brought the unfinished painting back to London with him. The second stage of the painting’s creation took place in London during the winter. Millais posed Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862) in the bathtub to complete the composition. Siddal, who was to become the wife of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was a frequent model for Millais.

Ophelia was initially exhibited at the Royal Academy to some acclaim and some criticism. The final picture stunned crowds at the Academy due in part to Ophelia’s unattractive nature, but also because of the tragic nature of the hopeless death. Ophelia became Millais most famous painting and one of the most important works in the cannon of art history.

Millais sold the work to Henry Farrer (1844-1903), in 1851. Farrer was an artist and art dealer, who studied under Dante Gabriel Rossetti before immigrating to American in the 1860s. In 1862, Ophelia changed hands again, as Farrer sold it to a collector, B. G. Windus, who had a fascination with Pre-Raphaelite artwork. In 1894, the work was part of Sir Henry Tate’s (1819-1899) original gift which formed the Tate Collection at the Tate Britain. Ophelia is not currently on display but belongs to the Tate Britain in London, England. When on display at the Tate Gallery it is has been hung next to Edward Burne-Jones’s (1833-1898) The Golden Stairs (1880).

Why did Millais paint Ophelia?

Ophelia was a popular subject at the Royal Academy. Shakespeare’s works were a popular subject to be recreated in painting. In particular, the Pre-Raphaelite’s championed Shakespeare’s work. This was, in part, due to his depiction of the natural world and his choice to relay complex emotional and moral plots. Pre-Raphaelite artists were attracted to Shakespeare’s poetically written death scenes because it allowed them to depict the tragic. Millais, like the rest of the Brotherhood, seemed to value the reading of Shakespeare over the viewing of the plays. They typically produced scenes that bore more resemblance to the actual text rather than the performed versions. This could account for Millais choice of this scene, which is not typically performed. However, Millais provided a rich textual description is present in the work.

Is Ophelia a romantic painting?

In a sense, yes because it taps into the romantic, if macabre, notion of being heartbroken over the death of a lover. Ophelia is so distraught after Hamlet’s death, that she cannot bear to be without him. Therefore, she allows herself to succumb to the cold water and drowns. However, it is not romantic in the traditional sense, or in relation to the artistic movement of Romanticism, which emphasized the sublime more than Pre-Raphaelites.

Other Depictions of “Ophelia”

Ophelia, as with other subjects from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, was a very popular subject for artists to paint in the 19th century. While depictions of Ophelia exist, what startled Victorian audiences is the exact moment of Ophelia’s story that Millais painted.

Arthur Hughes (1832-1915) and John William Waterhouse (1849-1917) both chose to create a painting of Ophelia still sitting on the willow branch, prior to it breaking and her falling into the water.

Alexandre Cabanel’s (1823-1889) image depicts Ophelia falling into the water, but she hasn’t quite fallen in and there is still some hope that she will reach the branch she grasps for and pull herself out.

In contrast, Millais’s Ophelia is the ultimate tragic romantic figure. Her fate has already been sealed and she has given into it. Additionally, Arthur Hughes depicted Ophelia in a more typically attractive way that fit the conventions of painting and Academy standards more than Millais’s painting.

Citations

- Poulson, Christine. “A Checklist of Pre-Raphaelite Illustrations of Shakespeare’s Plays.” The Burlington Magazine 122, no. 925 (1980): 244–50.

- Rhodes, Kimberly. Ophelia and Victorian Visual Culture: Representing Body Politics in the Nineteenth Century. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2017.

- Riggs, Terry ‘Ophelia,’ Sir John Everett Millais, Tate Gallery, (1998)